My oxygen fired ABS-pipe cannon

After having seen Ron Harding's potato cannon, I just had to take the sport to its full level of insanity!These photos are from some "tests" we performed on a precursor to the RIM BlackBerry ® in August 1998.

I designed this cannon to be fuelled with an oxygen/propane mixture. I wanted a fuelling system where I could see how much fuel I put in the cannon so I could control the mixture. I also wanted to be able to operate it without getting my hands near the cannon once it was fueled up, just in case the cannon would somehow trigger and explode unexpectedly.

I used a balloon to meter the fuel. Basically, a balloon

on a T-connector. One side of the T connects to the fuelling valve

on the cannon, while the other end is connected to the

end of my cheap welding torch.

I used a balloon to meter the fuel. Basically, a balloon

on a T-connector. One side of the T connects to the fuelling valve

on the cannon, while the other end is connected to the

end of my cheap welding torch.

I start with the valve on the cannon in closed position. I then fill the balloon with propane until it reaches about a 6 cm diameter. Next I add oxygen until it reaches twice that diameter. I start with the propane because it takes much less of it, and by adding the oxygen afterwards, I can be confident that the propane actually makes it into the cannon, as opposed to still being in the hose.

Priming the cannon - from a distance

Priming the cannon - from a distance

Next I open the fuelling valve to drain the balloon into the cannon.

I operate the valve from a distance using my ramrod. The ramrod has a slot

at the end of it for gripping the valve handle.

It's best to let the fuel into the cannon very

slowly so that the inflow of gas does not push the projectile forward

in the cannon barrel. The cannon also has a bit of a 'baffle' near the fuelling

valve to make sure the fuel does not 'shoot' through the chamber without mixing.

The ignition system took a few tries to get right. My first system consisted of two screws in the side of the ABS pipe, connected to a barbecue lighter. This system typically worked for the first shot. After that, condensation shorted out the screws enough to prevent a spark. The combustion products are carbon dioxide and water vapour, and the water vapour causes condensation. So I installed a spark plug, which is much better at maintaining insulation even with some condensation. But the barbecue lighter wasn't powerful enough, so I switched to using an ignition coil. The ignition coil has the advantage that the low voltage side, unlike the high voltage side, can be powered through a regular long wire, so the cannon can be triggered from a good distance.

Some of my projectiles - much better than potatoes!

Some of my projectiles - much better than potatoes!

I also came up with some fancy projectiles.

The problem with shooting potato slugs is that they are usually softer than

the target, so the potato disintegrates into a mist without necessarily

penetrating the target. So I made some nice aerodynamic projectiles

out of hardwood. Initial experiments indicated

that the projectiles tumbled in the air once they left the

cannon. So I made projectiles that were just short cylinders, seeing that

there was no point in making one end pointed.

Later on, I started putting a tail on the projectiles. This makes them aerodynamically stable so that the projectile continues to point forward. When loaded in the cannon, the head is in the barrel, while the tail sticks back into the combustion chamber. The photo shows some of my projectiles - before I shot them. The elaborate tail on the middle projectile turned out to be a complete waste of time. The tail fins didn't withstand the acceleration. After shooting it, the tail fins were still in the cannon's combustion chamber. The tail on the bottom right projectile also didn't work very well. It wasn't made of hardwood and just ripped apart when I shot it. A straight hardwood tail worked the best.

Loading the cannon with a ramrod

Loading the cannon with a ramrod

Here's me loading the cannon with the ramrod. The ramrod isn't

really necessary when shooting just a hardwood projectile - I always make

these so they slide in and out freely.

When putting wadding behind a projectile, or shooting potato slugs,

the ramrod comes in really handy to push the projectile down the barrel.

Note that the projectile is loaded before the cannon is fuelled.

I made some measurements of the muzzle velocity of the projectiles by shooting through two pieces of wire half a meter apart, and measuring the time interval between when the electrical circuits were interrupted. My measurements all came out to about 175 to 180 meters per second, or just over half the speed of sound.

With the projectiles traveling that fast, there is no point in shooting into the air. The projectiles move too fast to be seen. Shooting at a particular target at close range is much more fun.

Small pieces of electronics, like this Inter@ctive pager 950

(it wasn't yet called a BlackBerry) are ideal targets,

having so many components that can be dislodged on impact.

Numerous pager prototypes and answering machine have met an

entertaining end this way.

Small pieces of electronics, like this Inter@ctive pager 950

(it wasn't yet called a BlackBerry) are ideal targets,

having so many components that can be dislodged on impact.

Numerous pager prototypes and answering machine have met an

entertaining end this way.

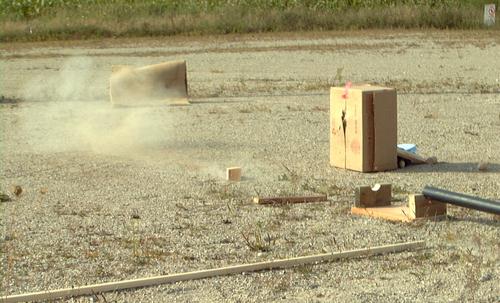

This shot was taken a fraction of a second after the shot.

The pager is gone, and the cannon has recoiled mostly out of the picture!

This shot was taken a fraction of a second after the shot.

The pager is gone, and the cannon has recoiled mostly out of the picture!

It appears we lost some of our test results in the corn field!

That corn field has since been turned into the University of Waterloo

Research and Technology park.

It appears we lost some of our test results in the corn field!

That corn field has since been turned into the University of Waterloo

Research and Technology park.

I think in this shot, the projectile got

deflected down from the impact, and went under the piece of carpet behind

the pager.

I think in this shot, the projectile got

deflected down from the impact, and went under the piece of carpet behind

the pager.

Smashed bits of pager. The Inter@ctive pager 950 actually stood up much better

than when we tested the tested the previous model

Smashed bits of pager. The Inter@ctive pager 950 actually stood up much better

than when we tested the tested the previous model

I put these pictures on a file server at work to show to some colleague who weren't there in person. Apparently, Mike Lazaridis while visiting Mark Church's office, wondered what would happen if the newer model was tested under extreme conditions. Mark told him that such tests had been performed already, and showed him the pictures! Fortunately, he was relatively cool with it, and I didn't get into trouble for it.

Bullet hole in 3/4" plywood

Bullet hole in 3/4" plywood

I also tested the cannon against some 3/4" plywood. When I shot a hardwood

projectile against it, it went straight through, and fairly cleanly. By

the shape of the hole, I'm pretty sure that by the time it hit the plywood, the

projectile was travelling sideways, and pointing down to the left. This was before

I started making projectiles with tails.

A potato shot at the same piece of plywood mostly became absorbed within the plys of the wood, although the plywood bulged and part of the potato sprayed through the cracks out the other side.

Result of shooting against the side of an old vehicle

Result of shooting against the side of an old vehicle

Shooting against the side of an old pickup truck

(the truck in this picture)

produced less spectacular results.

The sheet metal, because it is able to yield, is capable of absorbing a lot of energy

before it tears. It's interesting though how much paint got peeled cleanly off

from the impact. The indentation was about 2 cm deep from the original surface, and

extended to the edge of the peeled paint. But as the picture shows, the cannon

did less damage to the metal than a rust spot over 20 years.

A failure in the cannon barrel

A failure in the cannon barrel

It's interesting that the ABS pipe is able to withstand the abuse of

being used as a cannon at all. Before firing it for the first

time, I took numerous precautions to shield myself from a potential

shrapnel explosion. Over the course of numerous

'tests' I became more and more confident that the ABS would in fact hold

up. Nevertheless, after maybe 30 firings, the barrel cracked.

I had attached the barrel to the chamber using an ABS screw thread adapter,

shown here. I knew this was a weak link, but I figured that the chamber,

with its larger diameter would fail before the connector or barrel would.

I think what eventually happened is that the chamber always got bounced around by recoil, and eventually the thread connection snapped off. What is more surprising is that the 1.5" barrel actually developed a longitudinal crack. The barrel, with its smaller diameter, should experience significantly less stress than the chamber.

The comforting thing is that this failure did not result in any pieces flying off. I didn't immediately realize the barrel had cracked, so I was puzzled when the projectile came out so slow that it didn't even damage the target. My brother had videotaped that shot, and you could actually see the projectile flying - it was that slow! Most of the gasses had escaped though the crack which, no doubt, opened wide when the cannon was fired. I had previously experimented with breaking ABS, and the nice thing about it is that it yields considerably before it snaps. PVC on the other hand is much more prone to cracking, so the risk of pieces flying is much greater.

When I replaced the barrel, I bonded it directly into a 3" to 1.5" adapter piece, eliminating this weak spot. I haven't had any mechanical failures in that cannon since.

Back to the BlackBerry smashing page

![]()